Flight Identification of European Passerines and select landbirds

Tomasz Cofta

Princeton University Press WILDGuides | 2021

496 pp. | 16 x 24 cm

Paperback | £38 / $ 45 | ISBN: 9780691177571

Ever since its inception at the turn of the millennium, the WILDGuides series has repeatedly broken new ground in field guide concepts and production. From the championing of photographic guides and use of digital artwork, to coverage of overlooked taxonomic groups, the series has made a name for pushing the frontiers of field guide capability. The current title certainly follows that precedent. We have enjoyed flight identification guides to non-passerines for decades, but the practicalities of producing an illustrated guide to smaller, fluttery passerines are considerable. And would the birding public need or want such a guide? Well, the gauntlet has quietly been taken up and the book is out. I suspect WILDGuides have done it again by publishing another indispensable guide that we did not know we needed.

This is a large and detailed guide, slightly larger than Britain’s Birds and about the same weight. The book treats 205 passerines and 32 non-passerines, approximately one third of the number covered there, which gives some idea of the amount of space afforded each species. The book goes into considerably more detail on its subject than any other available guide, providing a wealth of information that will be of immediate interest to the vismig and nocmig communities, but with wider appeal to all keen birders who strive to improve their field identification skills.

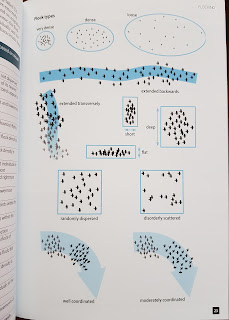

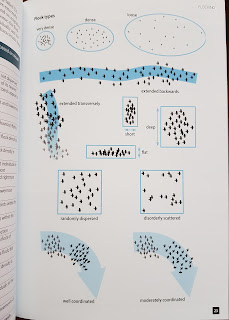

This is one book that benefits from a careful read of the introductory sections, which advise on how to use the guide and set out an important framework for analysing passerines in flight that covers structure and shape, colouration, flight characteristics, flock dynamics and vocalisations. These sections are worth studying because they break down the components that comprise each species’ flight signature and reinforce a habit of running through this checklist in order to identify birds. They also establish definitions that are used in the species identification accounts. Much of this information will be new to the average user and is worth digesting before proceeding to the species accounts.

It is worth at this point noting the author’s credentials. I first came across Tomasz Cofta’s striking bird illustrations while reviewing drafts of The World's Rarest Birds in 2012, when he stepped in to provide images of those 75 species that were so rare that no photograph existed. But, by his own account, Cofta has spent thousands of hours observing migrating birds, has ringed almost 100,000 individuals and published a hundred articles (mostly in Polish journals), so he should not lack the authority to produce such a book.

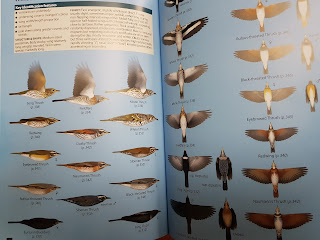

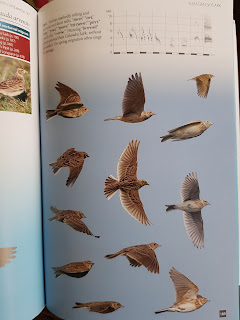

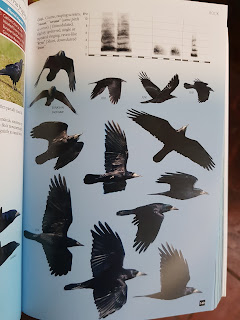

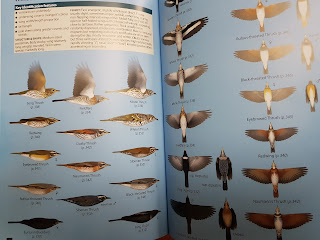

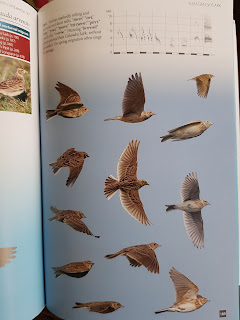

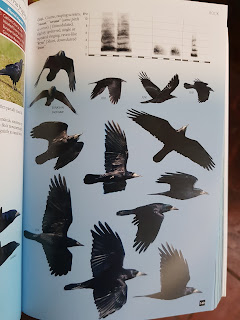

Each species account is typically constructed around digital artwork depicting the species from the side above and below supplemented by a gallery of photographs, 2400 in all, obtained under field conditions. The less than studio quality of the photographs, sometimes taken at odd angles, often backlit, occasionally blurry, counterbalances the meticulous precision of the paintings by capturing the sort of glimpses that one might snatch in field observations. That is not to say that many of the photographs are not of excellent quality. The combination of clean, precise artwork and field photographs works well in giving an idea of the flight jizz of most species.

The text is surprisingly detailed, longer than some field guide texts. Who would have guessed that there was so much to say about small birds in flight? There is a lot to digest here, and I confess I am still in that process, slowly reading through species of interest in order to assimilate new information.

Efforts have been made to compare similar species, so, for example, the section on thrushes nicely distinguishes each species on a combination of differences in tail length, flapping rate, flight-wave and flock size even without a the need to obtain a hint of colour.

Sound is at least as important as visual clues in identifying flying birds, and Cofta gets as close as it is possible to get in a book to a comprehensive description by triangulating transliterations of calls, sonograms, and a single QR code link to sound recordings hosted on the Princeton University Press Soundcloud website. Sonograms are a very powerful tool that have grown in popularity. They were virtually unheard of in British birding circles before the publication of the first volume of BWP in 1977, which confounded many buyers by including them. Perhaps the biggest boost to their popularity has come from the growing popularity of nocmig, where identification of flight calls by sonograms is routine. The only other other field guides that attempt comprehensive coverage of bird vocalisations by sonograms that I am aware of are Nathan Pieplow’s excellent Peterson field guides to North American birds, and I would love to see an equivalent for the Western Palaearctic.

In sum, this pioneering guide is a formidable reference tool for identifying passerines in flight. It will deepen the understanding of anyone interested in the subject, particularly vismig and nocmig enthusiasts, but also the garden patch birder straining to determine the identity of the smaller birds that fly over the house. A strong recommendation for anyone wanting to push their personal frontiers of bird identification.

References

Cramp, S. et al. (1997–1996) Handbook of the Birds of Europe, the Middle East And North Africa

Volumes 1–9. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Hirschfeld, E., Swash, A., & Still, R. (2013) The World's Rarest Birds. Princeton University Press WILDGuides, Oxfordshire.

Hume, R., Still, R., Swash, A. R., Harrop, H. & Tipling, D. (2020) Britain’s Birds. An Identification Guide to the Birds of Great Britain and Ireland. 2nd ed. Princeton University Press WILDGuides, Oxfordshire.

Pieplow, N. (2017) Peterson Field Guide to Bird Sounds of Eastern North America. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, Boston.

Pieplow, N. (2019) Peterson Field Guide to Bird Sounds of Western North America. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, Boston.