Britain’s Birds. An Identification Guide to the Birds of Great Britain and Ireland. Second Edition, fully revised and updated

Britain’s Birds. An Identification Guide to the Birds of Great Britain and Ireland. Second Edition, fully revised and updated

Rob Hume, Robert Still, Andy Swash, Hugh Harrop & David Tipling

Princeton University Press WILDGuides | 2020

576 pp. | 15 x 21 cm

Paperback | £20 / $ 35 | ISBN: 9780691199795

Despite commencing birding at a time when painted plates in field

guides left quite a lot to be desired, I have been slow to entirely

embrace photographic guides. My first was the

Collins Bird

Guide, “a revolutionary field guide” to the birds of Britain

and Europe, and it provided a welcome additional source of visual

material at a time when good quality photographs of birds were not

readily available, but I certainly never pressed it into action as a

field guide. The first publishers that seemed to be dealing with the

limitations of photographic material in order to take full advantage

of growing photographic libraries were WILDGuides in the UK and Kenn

Kaufmann in the USA. Both were skilfully manipulating selected images

in order to compensate for different light conditions, standardise

postures and eliminate artefacts of the photographic process. Both

publishers now have a long list of titles covering a wide range of

taxonomic groups, some of which have were sorely lacking in

identification literature, and many of these guides are now standard

identification works. However, the United Kingdom’s avifauna is

very well covered by a dizzying number of field guides, some of them

amongst the best guides to any avifauna in the world. A new guide

launched onto this crowded field has to be very good indeed if it is

to make any significant contribution. And

Britain’s Birds,

published in 2016, is, and it has.

I have had the first edition by my

bedside since that time. I typically pick it up at the end of the day

to resolve queries arising from the day’s encounters, and one

consultation generally leads on to another. After 40+ years of birding, I still

get puzzled or excited by something every day, and this book helps me

resolve doubts. It seems fitting that the first author, Rob Hume, has

been a familiar name from YOC/RSPB magazines since I began birding.

Rob’s co-authors together have truly formidable experience, not

only on this topic, but in photography, design and the production of

field guides. So the user is in very safe hands indeed.

Britain’s Birds is a large,

comprehensive field guide, approaching the size of many of the

standard Neotropical guides that cover avifaunas several times as

large. At 1.44 kg and nearly 600 pages, it could be reasonably

argued that this is not a field guide at all – indeed, my first

edition has never seen sun, shower or the shady inside of a backpack

– but then again, British birders of my generation were schooled to

leave all references at home, but rather to take detailed field

notes, something that I dutifully abide by to this day; and indeed,

being of a similar vintage, this is the process suggested by the

authors.For those who feel daunted by such a tome, or really do want a portable guide to take into the field, watch out for my review of the companion

British Birds, A Pocket guide.

Why so large? The authors cover all 631

species on the British and Irish lists as of the end of 2019, using

BOU/IRBC taxonomy which is in turn adopted from the IOC

World

Bird List (note

that, as Nigel Collar has

pointed out, IOC denotes the

“international

ornithological community”, not International Ornithological

Congress). Another 33 species are also covered. So a page per

species is about what one would expect for a visual guide to birds.

|

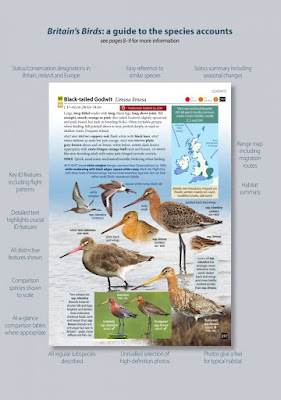

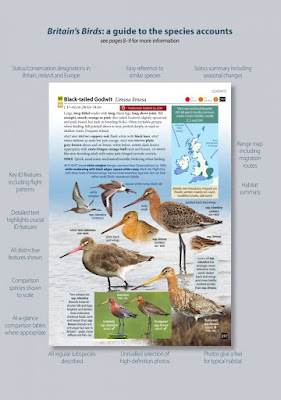

| A typical species account |

What about content? All regularly

occurring species are typically treated by a page of coverage which

includes text, photographs and a map. Birds are presented in their

habitat, giving an additional clue to their characteristics. Scarcer

species receive less space, while problematic groups, such as gulls,

enjoy expanded comparative sections. All plumages are included,

depicted with 3,591 photographs.

Maps are derived from current

BirdLife

International base maps, which were originally compiled by

BirdLife International and

Handbook of the Birds of the

World (the latter now defunct). They are a generous size that is

easy on the eye and permits high resolution. Arrows indicate broad

migration routes. Status, seasonality and population data appear

above the map, and habitat information below, allowing the user to

determine almost at a glance the chances that a particular species

has been seen.

Text is concise and, for me, achieves

that tricky balance between providing enough description to clinch

identification and avoiding extraneous detail. The team’s field

experience is much in evidence, with expert insight being employed to

craft succinct accounts that incorporate much distilled

identification knowledge. Capitals, bold text and italics help

navigate the sections.

Any downside? Having written field

guides myself, I have renewed respect for those who take on such a

task, and am now strangely reluctant to pick holes in the work of

others. The production of a work like this is a massive undertaking,

and all field guides contain errors, many of them spotted the day

after the galleys go to press. However, I would be hard pressed to

find much to complain about with this field guide, and remarkably

uncharitable to draw attention to anything I found. I had already

consulted the first edition on a daily basis, and – barring one

unfortunate but conspicuous photo mix-up in my first printing –

errors were few and far between, and the overall utility of the guide

simply swamps any gripes. This edition has corrected the few

oversights I had found and has improved the already high overall

quality in every respect. Doubtless Chris Batty’s role as an identification consultant will have eased the burden of verification (he kindly gave me the benefit of his formidable knowledge on one of my own field guides). As far as field guides to the British

avifauna are concerned, Svensson

et al.’s Collins field

guide and this current volume have, for me, become the two standard

works the I reach for first, and their very different approaches

complement each other nicely. If I need to delve beyond them, I reach

for Witherby, BWP, van Duivendijk, Beaman and Madge, Harris

et al.

or the relevant standard monograph.

Given that I view this as a must-have

for anyone with an interest in identifying the birds of the UK,

whatever their level of expertise, the question then becomes, “Should

owners of the first edition replace it with the second?”. That’s

a hard question to answer, and depends as much on the strength of

one’s bookcase shelves and the tolerance of one’s cohabitants as any

technical factors. The current edition incorporates 800+ new photos,

layout has been improved in key places and the entire production

looks to have been revised with a fine tooth comb. And, of course,

the list of taxa covered is bang up to date, reflecting the February

51st BOURC Report. So American ‘Taiga’ Merlin (

columbarius)

and Shorelark (

alpestris group) are covered, as are other

splits and additions over the past four years.

This

is yet another ground-breaking field guide from the WILDGuides

imprint, and an outstanding guide to Britain's birds for observers of

all levels. At a retail price of £20, this is an absolute bargain.

The authors and all contributors are to be heartily congratulated.

___________________

A typical double-spread species account, in this case for Dunlin

Calidris alpina, showing the major plumages encountered in Britain and Ireland, along with subspecific variation. This is a variable species, and a standard, common 'yardstick' shorebird, so the coverage will be useful for beginners as well as those who want try to determine which subspecies they are seeing. Note the map indicating migration routes, and table showing the months during which different subspecies may be encountered. All relevant information can be taken in at a glance.

The double-spread devoted to the White/Pied Wagtail

Motacilla alba complex has been completely overhauled in this edition. I still find

alba hard to clinch, despite having read and re-read all of the literature, coupled with hours spent staring in monochrome at borderline individuals, so have already interrogated these pages several times. Photographs have been selected to help people like me. Note the inclusion of

personata, new to Britain since the book's first edition.

Ducks in flight: handy double-spread guide to fieldmarks. The images are first class, and the spread has been slightly improved since the first edition, with subtle eye-guiding lines linking images of the same species. Similar comparison spreads are provided for other groups that requite critical flight identification, for example gulls, shorebirds, raptors – even larks.

Particularly tricky identification challenges are sometimes addressed by means of an extra page or two, in this case examining the similar

Apricaria golden plovers. Not quite as much has been made of differences in leg length/proportion and head pattern as I might have suggested, but nevertheless the key identification characters are well covered.